How Hospice Teams Drive Meaningful Moments at the End of Life

Introduction

Pancho just wanted one last lap around the track.

His heart was failing. I worried about the risks, the meaning, the safety, the weight of the request. At IDG we planned a way forward: a car show and a vehicle that could give rides to anyone able.

We brought a racing UTV to the nursing home. A lightweight off-road vehicle, open-sided with roll bars, easy to enter and safe at low speed. Residents gathered outside, smiling as the engine rumbled. We ran slow laps in the cleared parking lot.

He came outside, placed a hand on the hood, and whispered: “Fun.” That single word became the memory staff return to again and again. The ride wasn’t only his wish. It became a shared joy for the whole facility.

Hospice often begins with one simple question: “What would make today a good day?” The question anchors dignity therapy, which helps patients reflect on meaning and legacy (Chochinov, 2007), and aligns with person-centered outcomes research, which emphasizes tailoring care to individual values.

The answer might be woodworking or card night. Often, it’s simply not being alone. Sometimes, it’s the thrill of the racetrack.

When hospice is done well, “a good day” is not chance. It’s created by a team, an IDG, working together to make meaning possible. That’s what we were racing toward when Pancho touched the hood and whispered his truth.

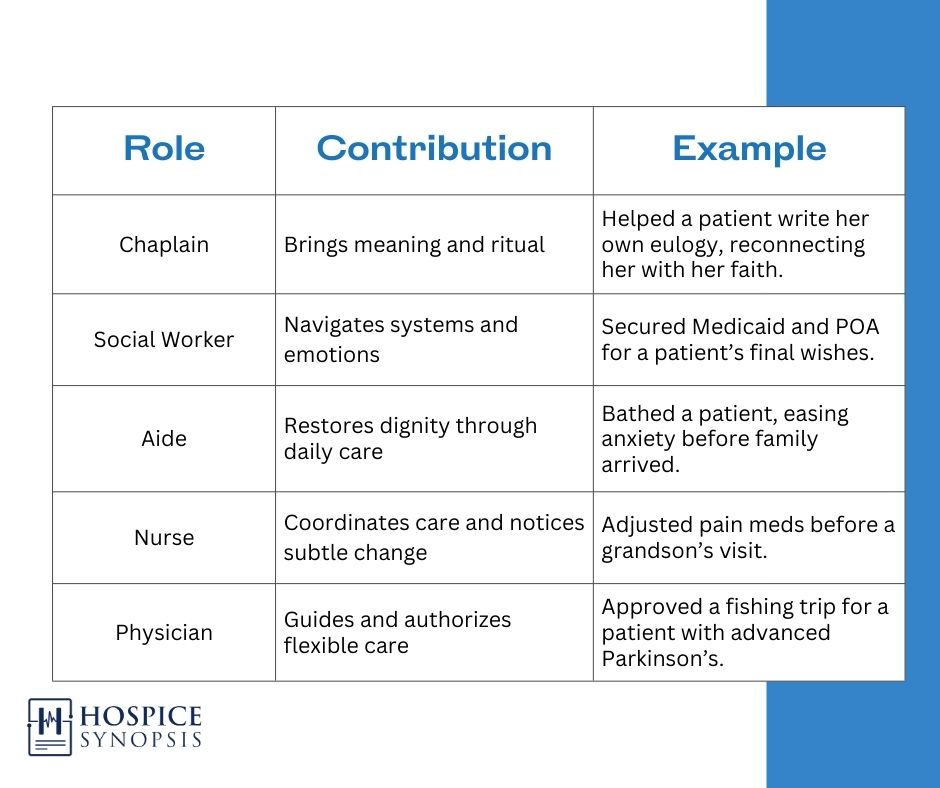

The Power of the Team: Who Shows Up, and Why It Matters

In hospice, care is never the work of one. It belongs to the interdisciplinary group (IDG). Each brings a distinct lens. Together, they steer the day toward peace.

When it works, it sounds like:

- A chaplain singing hymns bedside because the patient once led worship

- A social worker securing additional aide coverage from a payor

- A massage therapist easing agitation so meds aren’t needed as often

- A nurse finding a way to get a patient to her daughter’s backyard wedding

- A PA signing off and attending a boating trip for a patient with special needs

These moments rarely appear in the chart, but they shape what families remember as the why in “why hospice, why now”.

Moments That Made the Day: True Stories of Wishes Come True

- The Home Prom: A young woman with Huntington’s disease never got to go to prom. So her ECF team helped her pick a dress. Family decorated the commons. Staff showed up in suits. She danced the night away.

- The Final Adventure: A patient with two young children shared one wish: to create joyful memories at the zoo. The social worker and volunteer coordinator made it happen with help from our hospice foundation. A dolphin encounter and dinner. A weekend full of laughter.

- The Almost Missed Moment: We nearly missed a patient’s final porch visit because the DME vendor canceled last minute. The aide called three suppliers. The social worker drove 40 minutes to secure backup equipment. By nightfall, the patient sat under the stars with his brother. No chart could capture what that moment of mobility and freedom meant to the family.

These weren’t mapped routes. They were turns we took because someone asked, ‘Can we?’—and the team found a way. These moments answered the question: What would bring peace today?

These moments remind us that presence is the foundation of care, even when wishes can’t be fully realized. The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) offers resources to help teams navigate such challenges (nhpco.org).

The Good Day Loop: A Practice Worth Repeating

Good days don’t happen by accident. They happen when teams stay curious, responsive, and reflective. The Good Day Loop offers a rhythm for everyday care:

- Ask — What would make today a good day?

- Act — Try one thing, big or small.

- Reflect — What worked? What was missed?

- Care Plan — Document it. Build on it.

- Share — Who made it possible? What did it teach?

Quarterly Prompt for IDGs: Pick one good day story each quarter. Review it as a team. Teach it to new staff. Share it in a Legacy Round to build culture from lived examples.

Example: A nurse documented that a patient wanted to sit outside. The next week, the chaplain arranged music in the garden. What began as a line in the chart became a shared act of care.

Each Role, One Voice

Like driver and pit crew, each move depends on trust, timing, and a shared direction.

Closing Reflection: We Don’t Just Witness Good Days. We Build Them.

Hospice doesn’t always mean a ride around the track. Sometimes it’s motion brought to stillness. Sometimes it’s joy in a parking lot. Sometimes it’s presence when the plan falls apart.

Ask the question. Let the answers guide care. Some answers lead to joy. Some to stillness. Some to nothing at all. But asking still matters. Showing up still matters.

As Blog #1 reminded us: Think with the End in Mind. As the BigR reframes: focus on the high-leverage moments that build legacy. Good days in hospice are not accidents. They are the legacy of an IDG that asks, acts, and adapts together.

Three Key Insights

- The question “What would make today a good day?” is a compass for meaningful care.

- IDG members bring unique and essential tools to make moments matter.

- Hospice’s greatest impact is often in the non-medical moments it protects and makes possible.

Two Actionable Ideas

- Hold quarterly Legacy Rounds where each team member brings one story, one moment, or one line from a patient that brought meaning.

- Add a “Good Day” section to routine IDG documentation: what mattered, what was tried, what was noticed. Remember: You are not just documenting decline. You are helping someone live. Ask the question. Make the moment. Share the story.

One Quote

“In hospice, good days don’t happen by chance. They’re driven by presence, steered by trust, and tuned by teamwork.” — Brian H. Black, D.O.

Bibliography

- Chochinov, H. M. (2007). Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity-conserving care. BMJ, 335(7612), 184–187. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39244.650926.47

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2024). Standards of Practice for Hospice Programs. Retrieved from https://www.nhpco.org

Glossary

Dignity Therapy – A structured interview method that helps patients reflect on meaning, purpose, and legacy at the end of life.

Person-Centered Outcomes – Research and practices that measure success by how well care aligns with the individual patient’s values, not just clinical metrics.

Good Day Loop – A repeatable hospice practice framework of asking, acting, reflecting, documenting, and sharing patient-centered goals to create meaningful days.

Today Was a Good Day – A Hospice Synopsis phrase highlighting that small, values-driven interventions can define the impact of hospice care.

IDG Storyboard – A practice tool for capturing, teaching, and passing on good-day stories within the interdisciplinary group to shape culture and morale.

To Do: Future Project

The Good Day Tracker – A companion tool for IDGs to record, reflect, and share “good day” moments. Includes:

- Printable template for quotes, wishes, follow-through notes

- Weekly prompts for IDG morale and inspiration

- Integration into onboarding and staff storytelling efforts