The NYHA Still Matters

Every hospice nurse knows the moment: the patient gasps two steps after standing, already on oxygen, swollen despite diuretics, worsening each week. Families call it weakness. Hospitals call it criteria. We should name it New York Heart Scale (NYHA) Class IV with clinical clarity.

“NYHA Class IV” alone in the chart invites denials, audits, and mistrust. It was never a checkbox. Paired with PPS ≤40% and functional decline, it tells a tale. Without context, it erases that story and costs patients’ care. Much like other metrics that matter, NYHA remains essential in hospice: not a number, but a narrative of breath and function. It’s all about the score plus the story.

Case Example

Mr. Lowe, 78, a retired truck driver, had severe heart failure. His EF sat near 30%. His daughter asked, “Does that number mean he qualifies for hospice?”

What mattered wasn’t just a static EF. He became short of breath just pulling on his socks. He had two hospitalizations in 60 days. He had 10lbs of fluid gain, despite diuretics.

EF didn’t tell that story. However, NYHA classified it as Class IV, with symptoms present at rest. Paired with PPS 40% and documented declines. The record was clear, defensible, and compassionate. His daughter finally understood: “his heart can’t get him through the day anymore.” She was right, it’s not just about numbers.

The Essentials

Definition. NYHA is a four-class system quantifying functional limits in heart failure:

- Class I: No symptoms with ordinary activity

- Class II: Symptoms with ordinary activity

- Class III: Symptoms with less-than-ordinary activity

- Class IV: Symptoms at rest

Nature. NYHA is subjective. It depends on clinician judgment, patient report, and observed capacity. It predicts mortality, but reproducibility suffers from interobserver variability.

Theme. NYHA is essential but insufficient. Alone it misleads. In context it clarifies.

Application. “Symptoms at rest” is the textbook line, but Class IV is broader:

- Minimal effort counts. Even standing, dressing, or talking may trigger symptoms.

- Not just dyspnea. Fatigue, palpitations, and angina also qualify.

- Fluid symptoms count. Orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, bendopenia.

- Dynamic status. Patients may fluctuate between III and IV; document the worst functional state.

- Prognosis. Class IV signals poor survival, but hospice eligibility still requires PPS ≤40%, weight loss, or hospitalizations.

At the bedside, Class IV means:

- “Patient breathless pulling on socks.”

- “Requires chair after 10–15 feet.”

- “Needs 2–3 pillows to sleep.”

NYHA IV should always be written as lived narrative, not just noted simply as “at rest.”

History

NYHA classification first appeared in 1928, refined in 1964 and 1994. Why has it lasted nearly a century? Not for perfection. It is subjective and inconsistent. It lasted because it is simple, human, and functional.

Before PPS or ECOG, cardiology needed a way to say what patients could do and what they could not. NYHA gave that answer. Hospice inherits the same need: a language of limitation understood in the clinic, in the living room, and in audits.

Clinical Relevance

In advanced heart failure, NYHA still provides clarity:

- Class IV signals serious limitation, usually with PPS <50%.

- CMS LCDs cite NYHA IV plus decline markers: hospitalizations, EF <20%, weight loss.

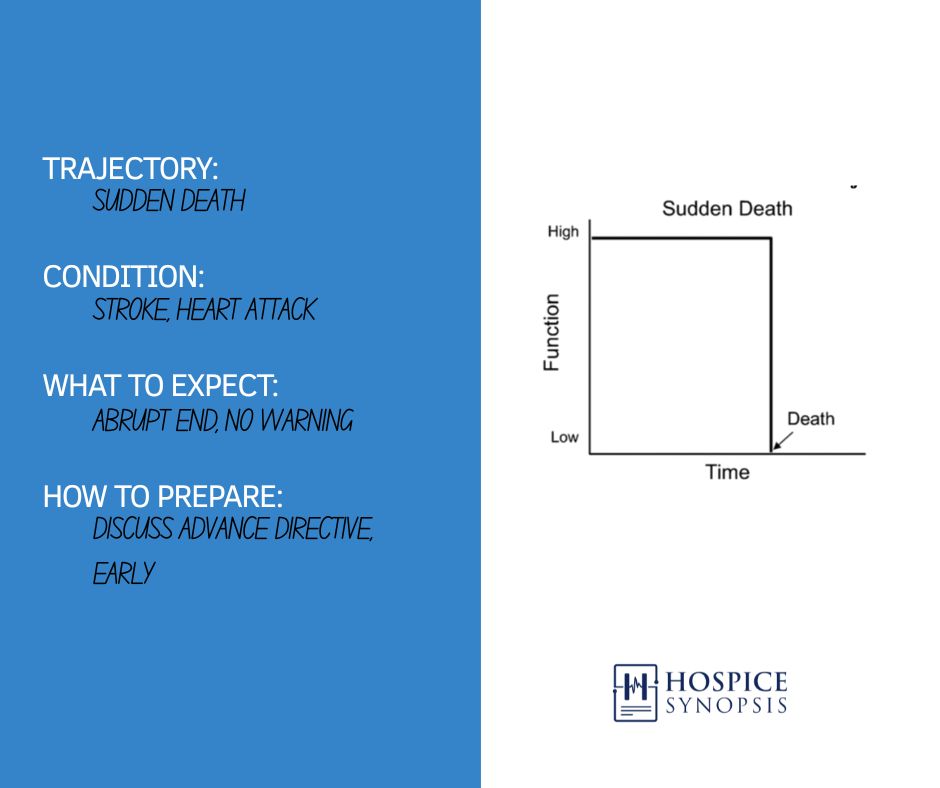

- Ejection Fraction (EF) is often a lagging indicator. Echo numbers may look stable or go unmeasured while patients continue to decline. Functional change over time always carries more prognostic weight.

- Families and physicians outside hospice know the scale, making it a bridge between worlds.

- Scope: Validated in HF and valvular disease, sometimes in congenital or right-sided failure. For non-cardiac illness, use tools like PPS or FAST.

Used wisely, NYHA supports eligibility, teaches teams, and reassures families that what they see is real.

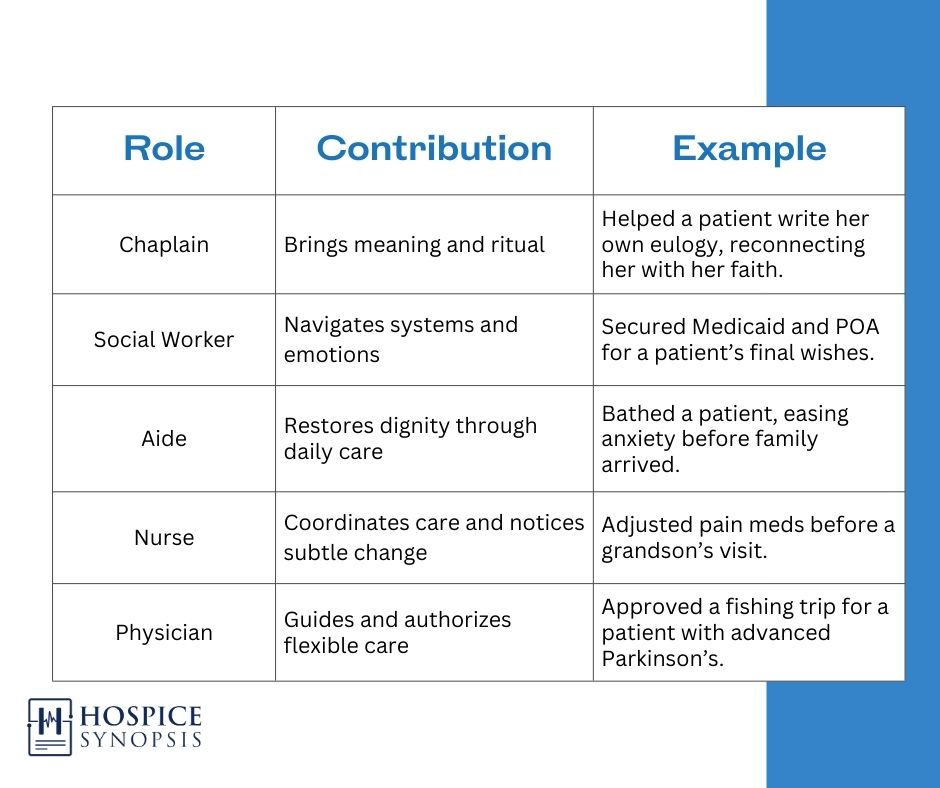

Interdisciplinary Voice

What each discipline brings to NYHA:

- Nurse: Record distance and recovery. “Needs two rests in 15 feet.”

- Social Worker: Capture role loss. “Stopped grocery shopping due to breathlessness.”

- Chaplain: Note spiritual or community loss. “Unable to attend church after 50 years.”

- Physician/NP/PA: Synthesize. “NYHA IV, PPS 40%, 5% weight loss, two CHF admissions, decline consistent with terminal heart failure.”

In IDG, NYHA language should not sit only in the physician’s note. When nurses, social workers, and chaplains mention the same functional language: dyspneic at rest, limited to 10 feet. Then whole record speaks with one voice.

Number + Narrative

NYHA should always be Number + Narrative.

- Number: Class I–IV

- Narrative: Functional loss proving the class

Examples:

- “NYHA IV, dyspneic at rest, PPS 40%, two CHF admissions, 5% weight loss in 3 months.”

- “Paused twice in 10 feet, needed chair after 20 seconds standing.”

Pair with PPS and weight trends to strengthen eligibility notes. Never rely on EF alone. Function carries more prognostic weight.

Beyond Self-Report: Anchors That Hold

NYHA is subjective. Frail or cognitively impaired patients may understate symptoms or forget limits. To anchor classification:

- Use proxy reports from caregivers.

- Document observed tasks: “Paused twice in 10 feet, needed chair after 20 seconds standing.”

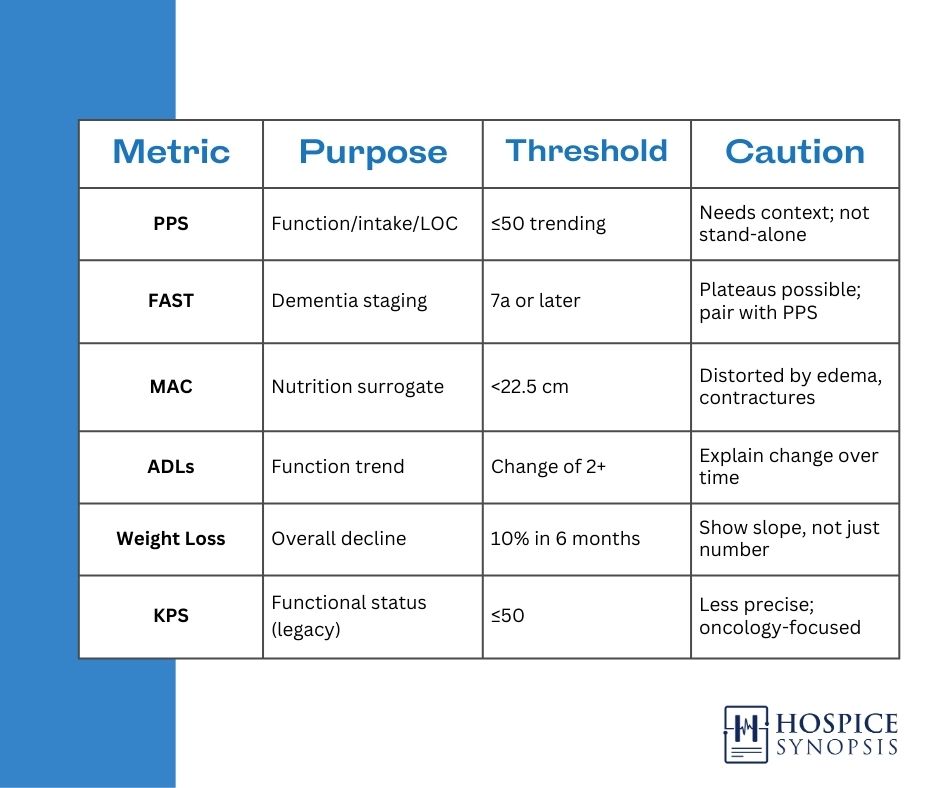

- Add objective tools: PPS, FAST, etc…

Anchors improve reproducibility and strengthen eligibility notes.

Blind Spots and Misuse

- Equating EF with prognosis: Low EF alone does not qualify. Function drives prognosis.

- Confusing PPS with NYHA: PPS is global; NYHA is disease-specific. They complement, not replace, each other.

- Assuming Class IV is enough: Documentation must show decline over time.

- Over-jargon in charting: “NYHA IV” without narrative is not defensible.

Compliance pitfall: A chart that only says “NYHA IV” is not very helpful. In audits, NYHA without narrative is treated as noncompliant. Eligibility rests on narrative: distance, frequency, functional loss. Without it, coverage and credibility collapse.

Say This / Not That

| Say This | Not That |

“NYHA IV, dyspneic at rest; PPS 40%; unable to walk 10 feet; two hospitalizations this year.” | “NYHA IV.” |

“EF 25% with functional collapse, symptoms now daily at rest.” | “Low EF, so hospice.” |

“Decline in activity and self-care, no longer dresses without stopping for breath.” | “PPS 40%, meets criteria.” |

“Observed dyspnea after 8–10 feet, accessory muscle use, needed chair after 20 seconds, PPS 30%.” | “Nonverbal patient, severe CHF.” |

Closing

NYHA is essential but insufficient. Alone it risks becoming a checkbox that hides truth. Paired with PPS, weight loss, and hospitalizations, it tells a story of decline families and auditors can trust.

Like PPS and FAST, NYHA follows our Hospice Synopsis rule: every metric must live through story. The number points. The story proves.

When decline is measured, NYHA gives us the language. Our job is to add the narrative that makes hospice clear today.

3 Key Insights

- NYHA remains one of the oldest and clearest functional tools in heart failure, still vital in hospice.

- It is subjective. Anchor it with PPS, weight loss, and observed decline.

- A number alone fails. Narrative makes eligibility defensible and care plans clear.

2 Actionable Ideas

- Standardize CHF notes: always pair NYHA with PPS and recent hospitalizations.

- Teach every IDG member how their notes shape NYHA class.

1 Compassionate Call to Action

Use NYHA not as a checkbox but as a bridge. Turn breathlessness into language that families, teams, and auditors can trust.

“Breathless at ten feet tells a truer story than EF alone. NYHA gives us the words; PPS and trajectory make them matter.”

Bibliography

- The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association. (1994). Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels (9th ed.). Little, Brown & Co.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2025). Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Hospice – Heart Disease. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database

- Levy, W. C., Mozaffarian, D., Linker, D. T., et al. (2006). The Seattle Heart Failure Model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation, 113(11), 1424–1433. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102

- O’Connor, C. M., & Whellan, D. J. (2005). Evolving role of functional classification in heart failure: NYHA and beyond. American Heart Journal, 149(2), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.010

Glossary Terms

- NYHA (new): The New York Heart Association classification—a four-stage functional system (I–IV) originally designed for heart failure, still used in hospice to document decline and support eligibility.

- Class IV Heart Failure (new): The most severe NYHA stage, defined by symptoms at rest. In hospice, often paired with PPS <50% and recurrent hospitalizations to support eligibility.